Battalion History

The Hoya Battalion, Georgetown University’s Army Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) Program, is steeped in a rich and enviable history that dates back to the birth of both the University and the United States of America.[1]

Although the first Corps of Cadets is believed to have officially begun in the 1830’s, the cadets’ soldierly spirit was evident as early as 1789. From the beginning, Georgetown students have exhibited such esteemed leadership traits as discipline, selfless service, good citizenship, personal pride, courage, and military bearing. These characteristics complemented the Jesuit tradition of military virtue that began with the Society’s founder, Ignatius of Loyola.

Even George Washington, that great citizen, soldier, and father of our nation, admired the military quality of Georgetown’s sons.[2] While parading through George Town in 1796, Washington stopped to admire the College boys, “…all formed in a line on the north side of the street (Water Street). They were dressed in uniforms consisting in part of blue coats and red waist-coats and presented a fine appearance. They seemed to attract the attention of the general very much.”[3] Washington was received a few weeks later at Georgetown’s campus when he came to visit two of his nephews. He reviewed the boys and their uniforms a bit more closely this time. Afterwards, he addressed the assembled crowd in Old North and began a tradition of Presidential visits to campus which is carried on today.

Even though they were not called cadets, Georgetown’s earliest students looked like cadets and behaved like cadets. They were proud of America’s successful revolution and excited for their new nation and its leaders.

Perhaps the most entertaining anecdote surrounds the visit of the French General Marquis de Lafayette to Washington, D.C. in mid-October 1824. Lafayette famously aided Washington and the colonials in the fight for independence. When he returned to visit the new capital, the citizenry prepared a parade and gave Georgetown the place of honor. Dr. DeLoughery of the class of 1826 wrote the best recollection of the story shortly before he died. He said,

”… I cannot close these remarks without relating an event which occurred during the visit of General Lafayette to Washington. There was to be a reception at the Capitol, and the boys were to take part in the procession. As Georgetown College was the oldest institution of learning in the District we were assigned the precedence in the ranks. Now there was also the Columbian College (present-day George Washington University), and belonging to it were more large boys or young men, than we could boast of, although the number of students by no means equaled ours. Columbian thought that it should be placed first, and not being able to persuade the marshal to yield to its wishes, determined to occupy the first place by main force. So no sooner was the order given to advance than a party of the Columbian boys, bearing a beautiful flag, the gift of the ladies of Washington, rushed forward to pass us, and they did so, placed the star that surmounted their banner beneath our little flag and cut it completely from its staff. In an instant a number of our larger boys, seeing what had been done made a spring at their banner, and tore it down and bore it off. I remember distinctly that the star fell near me, and that I crushed it under my feet. Order was soon restored, we took our places, and the Columbian boys, I believe, returned.

Some three days later, Lafayette was to be received by the citizens of Georgetown, and of course a visit to the college was a part of the program. On this occasion we marched down Bridge Street to the stream which separates Georgetown from Washington, and there met him.

On our return what was our surprise at seeing our lost flag floating on a little two-story frame building. At once a number of the boys made a rush for it, obtained it, and bore it aloft in triumph to the college.

In commemoration of these events we had a banner painted by an artist named Simpson, representing on one side an eagle holding in its beak a streamer on which was inscribed the motto, “Nemini Cedimus;” on the reverse side the coat of arms of the college was placed. What trophies we had carried off from our opponents were afterwards restored. In conversation with Father Curley, I think he told me he had seen our banner or heard it spoken of when he entered the college some two years after. What has become of it I know not, but if there should be any record of the origin of the motto it will now be evident.”[4]

The Latin phrase nemini cedimus translates to mean, “Yield to no one.” It is a motto as appropriate for cadet use today as it was in 1824.

On January 6, 1831, the College’s young students displayed their proficiency in military drill for President Andrew Jackson. They marched in formation from George Town to the White House in splendid uniforms. They paraded for the President, whose nephew was enrolled at the college, and attended an address. Jackson “…praised their modesty, discipline, and studious character; then he exhorted them not in future life to disappoint the hopes entertained in regard to them by their professors and their country.”[5] The President received them in the White House’s Eastern room. Thereafter they marched to the Capital, visited the dome, and began the return route to the College. “Their number, drill, and conduct excit(ed) favorable notice in the city.”[6] Later, Georgetown cadets would parade and drill for both Presidents Buchanan and Andrew Johnson.[7]

Five years later some Georgetown students began to call themselves cadets. One student, Robert Alymer of Petersburg, Virginia, wrote home to his parents:

“The boys are at present organizing a company which is to be called the College Cadets; the uniform is the same as the College uniform, with the exception of a red sash, the pantaloons to be trimmed with a red braid, and a star on the left breast. We have spears in the place of guns. Our captain is one of the boys who was here the year before last and has just returned from fighting the Indians in Florida.”[8]

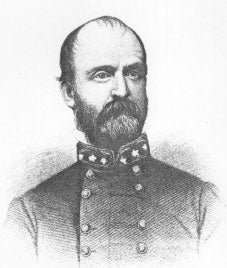

It is likely that two of the original members of this group were Lewis A. Armistead and Henry Heth. Both Armistead and Heth graduated from Georgetown in the class of 1837. Heth was the valedictorian, and he took a commission in the Army soon after he left the College. Eventually, he became a Major General in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War. He led a division of A.P. Hill’s Corps at Gettysburg, where he was wounded on the battlefield.

Armistead may even have been the first captain of the College Cadets. He had been a cadet at West Point, but was asked to leave after he broke a plate over Jubal Early’s head one day in the mess hall. He ended up at Georgetown, where his experience at the U.S. Military Academy would have been essential to the creation of a newborn cadet company. In addition, Robert Alymer wrote that the first captain had fought the Indians in Florida. Armistead was known to have served in the Seminole War during the same time period.[9] Later, Armistead would serve with great distinction as a Brigadier General in the Confederate States Army.

Armistead may even have been the first captain of the College Cadets. He had been a cadet at West Point, but was asked to leave after he broke a plate over Jubal Early’s head one day in the mess hall. He ended up at Georgetown, where his experience at the U.S. Military Academy would have been essential to the creation of a newborn cadet company. In addition, Robert Alymer wrote that the first captain had fought the Indians in Florida. Armistead was known to have served in the Seminole War during the same time period.[9] Later, Armistead would serve with great distinction as a Brigadier General in the Confederate States Army.

The Georgetown College Cadets, who had been organized in 1836, do not appear to have kept records until 1851. One year later, the cadets wrote a constitution that imposed a strict code of conduct upon its members.[10] Although the College retained some ultimate level of administrative control, the cadets governed and policed themselves. They imposed fines upon peers who, among many other things, spoke out of turn at meetings, disobeyed a superior, or handled a weapon improperly. The constitution even outlined procedures for the care of cadet rifles. In fact, the corps’ first allotment of rifles became a major issue, as the government was not in the habit of giving weapons to civilian college boys. Reverend James Clark, who had graduated from West Point in 1829, was able to secure rifles for a cadet armory. But in order to do so, the College Cadets had to become a volunteer militia.[11] So on the 13th of June, 1838, the Secretary of War approved ”Regulations for the issue of arms to the Militia of the District of Columbia.”[12] Thus, Georgetown’s corps of cadets became the oldest military unit in D.C.[13]

The cadets adopted a new uniform this year. The standard college uniform consisted of black jacket with dark blue pants and a black vest. During the summer, the college students wore the same jacket with white pants and a white vest. The College Cadets adjusted this uniform only slightly, adding gold braid along the pant leg and a military cap.[14] Unfortunately, the cadets would soon be faced with another change in uniform. They would choose between the Union blue and the Confederate gray.

As the Civil War approached, the nation’s boiling emotions affected the campus dearly. Georgetown, located in the Federal capital, was attended mostly by southern students and this sometimes caused tension. In 1861 a U.S. Army engineer visited the College to survey the area from the school’s lofty windows. A Georgetown graduate accompanied Captain E. F. Prime but this did not ensure a warm welcome. The Southern students surrounded their horses and lined the road to the school building. As the officer rode between the ranks, a tall Texan youth stepped to the front, waved his cap in the air, and yelled, “Three cheers for Jeff Davis and the Southern Confederacy!” The lines responded with a deafening roar. Captain Prime gracefully smiled and exclaimed, “Hurrah! Boys, Hurrah! I was once a boy myself.”[15]

But Georgetown’s involvement in the Civil War was far more serious than this anecdote reveals. The war divided the student body and pitted brother against brother. Approximately 1100 students and faculty fought, 200 for the Union and 900 for the Confederacy. 358 Georgetown cadets are included in this number. A few were veterans of the Seminole War who knew the horrors of combat. Many were college freshmen with no military training other than the year they had spent as a member of the College Cadets. Some of our cadets who fought in the Civil War were the youngest soldiers to see combat in Hoya Battalion history. Sadly, 117 cadets died during the conflict.

Cadet John Dooley answered the Confederacy’s call to arms and enlisted. A native of Virginia, Dooley fought until he was captured during Pickett’s charge at Gettysburg. He spent the rest of the war in a Union prison. Following the peace at Appomattox, Dooley returned to Georgetown and studied to become a Jesuit.[16]

After the war, most students returned to the hilltop to meet again with former classmates who had since become former enemies. Georgetown started the slow process of rebuilding a community that had straddled the battle lines and been torn bitterly in half by war. They began by designating the school’s colors blue and gray in commemoration of the service given by her sons to their respective states. Many other Georgetown traditions stem from this period in our nation’s history.

The cadets returned to a regular schedule of parades and reviews, as well as sharpshooting and drill competitions. Yearly events were held either on Thanksgiving or May Day. But enthusiasm for military service had dwindled because the horrible memory of the war lingered. One student recalled that, “drill was not very popular, for there was no great military spirit among the boys.”[17] Altogether less than ten percent of the student body participated and college authorities had begun to relax their support for the corps. The unit lost cohesion when Ulysses S. Grant became President in 1869 and again when General George Tecumseh Sherman spoke at the commencement exercises in 1871. The cadet corps was still composed of a predominance of southern students, and they were understandably reluctant to kowtow to the conqueror of Lee or the man who burned through the south to the sea.[18] The cadet organization gradually disintegrated, although over the next two decades it would experience several attempted (yet ineffective) revivals.

The Georgetown cadet corps does not return to earlier levels of strength and coordination until the late 1880’s. The cadets ran a competitive drill and a formal military banquet in these years. They formed as the honor guard in the college’s centennial exercises in 1889. But the program was still student-run. If a cadet desired to become an officer, they had to matriculate to West Point or attend an Officer Candidate’s School at Fort Myer.

World War I would change everything. The turmoil in Europe worried Georgetown students such that the University President, W. Coleman Nevils, S.J. was forced to ask the War Department to establish a Students’ Army Training Corps on the hilltop. However Nevils, not wanting to wait on the government, allowed the expansion of the cadet corps. On 18 December 1918, after two years of petitioning, his request was approved and the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps officially came to Georgetown.[19] The first unit was designated an Infantry Unit Senior Division, which meant that cadets commissioned from Georgetown could only enter the Infantry. Later, a Medical Corps and a Naval ROTC would be organized.

Over two thousand Georgetown men served in the First World War. It is uncertain how many of them had been cadets, but many certainly were. Among the group were many distinguished soldiers, including Denis R. Dowd, the first American to die in World War I.[20]

During the inter-bellum period, the cadets returned to the same schedule of training and drill that it had after the Civil War. It celebrated an annual Military Day on May 1, similar to the earlier May Day events. The Infantry Unit competed in many competitions and did quite well. In 1923 and 1940 their Rifle Team won the National Intercollegiate Championship, and between 1925 and 1927 they were twice named one of ROTC’s distinguished units.[21]

As the Second World War approached, it became clear to the War Department that ROTC would not fulfill the national demand for officers. So in May 1943, the advanced course in ROTC was suspended and basic course graduates were immediately sent to OCS so they could be commissioned sooner. In fact, all University courses were suspended during the war, so that the Georgetown campus could become a center for Army specialized training. Thousands of soldier trainees received instruction at Georgetown before heading off to fight.[22]

As the Second World War approached, it became clear to the War Department that ROTC would not fulfill the national demand for officers. So in May 1943, the advanced course in ROTC was suspended and basic course graduates were immediately sent to OCS so they could be commissioned sooner. In fact, all University courses were suspended during the war, so that the Georgetown campus could become a center for Army specialized training. Thousands of soldier trainees received instruction at Georgetown before heading off to fight.[22]

WWII, more than any other war, took the highest toll on Georgetown’s ranks. 171 were lost, including John Paul Beall and Al Blozis. Beall was the honor graduate of the Infantry ROTC in 1941. He became a Captain, the youngest Company Commander in the 9th Division. He participated in the U.S. coastal invasion of Algeria and was killed in action in Tunisia, 25 April 1943. Blozis was, until the 1980’s, Georgetown’s most famous athlete. He held the world record in the shotput and other field events, and had led the Hoya football team to national prominence.[23] He was commissioned at Fort Benning’s OCS and was sent to lead patrols along the enemy lines in the snowy Vosges mountains above Colmar, France. On his very first day, Blozis set out alone in a snowstorm to find two of his soldiers that had been separated from the unit during a firefight earlier that day. He never returned.[24]

Georgetown’s weary recovery from war brought major reorganization to ROTC. The newly organized Department of Defense opened an Air Force program at Georgetown. At some point the Naval ROTC moved to GWU, and in 1950 Air Force relocated to the University of Maryland.[25] The various branches at the Pentagon realized that they should consolidate their D.C. area ROTC programs to minimize operating costs. In 1964, the District’s colleges facilitated this effort when they founded the Consortium of Universities of the Washington Metropolitan Area. The Consortium’s mission was and is to support cooperative endeavors no single institution could accomplish by itself. It remains central to the Hoya Battalion’s efforts because it allows students at other schools to enroll in Army ROTC at Georgetown.[26] Since 1964, the Hoya Battalion has welcomed distinguished cadets from The American University, The Catholic University of America, The George Washington University, Marymount University, and the University of Maryland. These schools and their students have become essential members of the Hoya Battalion community.

During the Korean War the Hoya Battalion lost one of its shining stars. Harry W. Spraker, Jr. had been the Cadet Lieutenant Colonel in command of the corps at Georgetown before he graduated in 1950. He was commissioned and sent to the front lines of the United Nations police action in Korea. He earned the Bronze Star and Silver Star before being killed in action at Cnonchog on 4 February 1951. After his death, the cadets at Georgetown decided to name the rifle drill team after him. The Spraker Rifles, as they are now known, have competed all across the United States in challenging drill competitions. For many years, they sponsored and managed the United States High School Rifle Drill Championship and on a few occasions they won prestigious trophies. But most importantly, the Spraker Rifles became a vibrant co-ed social organization that brought many students and cadets closer together outside of class. It has been the closest to a fraternity or sorority that the Hoya Battalion has known, and many of the friendships made in the Spraker Rifles have lasted for decades.

But despite their dedication and hours of practice, the Spraker Rifles occasionally made mistakes. On 11 October, 1962, Hollywood’s latest military film, “The Longest Day,” made its premiere at Washington’s Ontario Theater. The red carpet debut brought out celebrities and politicians, and the Spraker Rifles were invited to perform. As women screamed when actor and song-writer Paul Anka and actor Henry Fonda arrived, Georgetown ROTC cadets prepared to honor the event’s attendees. They fired three volleys before they fixed their bayonets and began to pace the entrance to the theater. The unit’s captain halted the group and put them through the manual of arms, impressing the audience. United States Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the famous brother of a very famous president, was accompanied by his wife as they began to walk towards the performance. Cadet Sergeant Gerard Gallagher accidentally stabbed Kennedy’s arm with a bayonet when the couple stepped on the carpet. Gallagher’s face went pale as he said to his teammates, “I got one.” Kennedy needed no medical attention but Gallagher was shaken by the experience nonetheless. He confided to another cadet later, “He just turned around and looked at me kind of curiously, rubbed his arm and walk(ed) on.”[27] The embarrassing episode made the front page of the Washington Post the next morning.

During the sixties and seventies, the Vietnam War marked a turning point in the Army ROTC program at Georgetown. The anti-war and pacifist spirit had reached the D.C. University campuses and caused many students and faculty to revolt against University support for the program. In 1968, a group of students hired an airplane to shower the University graduation audience with leaflets protesting the war and pointing out that the audience could have been Vietnamese civilians showered with napalm. This stirred many to ponder ROTC’s role in college. Many students began to question the close relationship that the University and the Army had enjoyed, asking whether or not it was immoral for a religiously minded school to give credit for military training.[28]

In 1969, the ROTC issue began to divide Georgetown’s campus. An organization of 50 students occupied the ROTC offices during a three-hour-long sit-in. These non-violent protestors handed out anti-ROTC paraphernalia and showed films in the hallway outside the suite of offices on the second floor of the Old North building. About 59 cadets were on ROTC scholarships at the time, and they joined with sympathetic students in forming a Committee to Defend ROTC. A student referendum showed that about 68% of students wanted ROTC to remain on campus. But some student publications, like The Hoya, cried out against ROTC because they saw it as compromising the University’s neutrality and religious foundation. In 1970 some students and faculty disrupted ROTC classes so much that they were cancelled, and after harsh debate, Georgetown discontinued academic credit for the courses.[29]

Three years later, the issue was raised again when the School of Foreign Service proposed making ROTC its own academic department and giving its students limited academic credit. It seemed the university was ready to accredit ROTC because it feared losing an estimated $500,000 in federal scholarships and grants. Several opponents, especially Fr. Richard McSorley and Fr. Jerry Hall, S.J., framed their argument in strictly moral terms. McSorley said, “I am opposed to the destruction of life. I’m opposed to educators using their facilities to promote that.” Hall alleged, “The ROTC is not here to teach or train officers, they are here to make militarism more acceptable.”[30] These two Jesuits and a student named John Lyddy led a week-long hunger strike to draw attention to the decision. Colonel Albert Loy, who was then the Professor of Military Science, felt that protestors were taking the issue “out of context” and emphasized that ROTC courses met every academic standard and therefore deserved credit. Air Force ROTC Captain Herman Few restated Loy’s views, “The only issue is whether we should get credit. The moral issue belongs to the individual to decide on his own.”[31] The proposal was at first turned down, but it was accepted a few years later when Georgetown President Fr. Robert J. Henle, S.J. approved 6 credits for cadets in their senior year and organized ROTC as its own academic department. But a rift between ROTC and the University was nonetheless apparent, as the unit gradually saw its offices move further from the center of campus.

Although the seventies were a trying time for the Hoya Battalion, the years following 1972 brought the invaluable addition of female leadership to Georgetown’s cadet corps. Heretofore women were not eligible for entry into ROTC and female commissioned officers were quite rare. Ladies jumped at the opportunities that had previously been reserved only for male cadets, and took full advantage of ROTC benefits. Female participation in ROTC constituted roughly 20% of all cadets in the program during this decade. Christine Vaishvila was one of the Hoya Battalion’s first female cadets to graduate from the U.S. Army’s Airborne School. She was determined to overcome the Army’s challenges, remarking, “In the military, women have twice the amount of pressure to perform and really do their best.”[32] From the start, a female cadet’s commitment to the defense of the nation has shown no difference from that of any other cadet. When asked about the possibility of going to war, cadet Lizanne Siccardi commented, “I know I’d be scared to death. Anybody would. But if I had to, I’d go. Freedom of thought and expression, my family and my lifestyle – they all mean a lot to me. I’d be willing to fight for them if I had to.”[33] Female cadets have lent strong leadership to the cadet corps, as several have commanded the Hoya Battalion.

In the last two decades, ROTC has grown tremendously. It has become increasingly more formalized while it forged leadership for an Army made up entirely of volunteers. It has consistently placed among the top 100 Army ROTC units in the country, as its cadets lead the way in national evaluation. Indeed, the Hoya Battalion added two more national championships to its trophy case when it won the AUSA Army Ten-Miler running race in 1998 and 2000.

The Hoya Battalion remains one of the nation’s oldest sources of commissioned officers and can claim a tradition as proud as that of any military academy. It has commissioned over 4,000 men and women since 1918, and many other former Georgetown cadets led soldiers in battle before that.Its history is linked tightly to the heart of our nation, Washington D.C., and mirrors the growth of the country itself. But most of all, the Hoya Battalion has been and will be all that its cadets contribute to it. If the past is at all indicative of the future, Hoya Battalion cadets will continue to figure prominently in University life, the defense of Constitution, and their personal successes.

Alec D. Barker

Washington, DC, 20001

[1] N.B. This history incorporates the efforts of SGT Wayne Bailey, The Hoya Battalion’s supply sergeant between 1999 and 2001. A great debt is also owed to Lynn Conway, Georgetown’s Archivist, and the GU Archives staff at Lauinger Library.

[2]Georgetown was a single-sex institution until the twentieth century.

[3] “History of the R.O.T.C.” Ye Domesday Booke, 31, 1932.

[4] “Reminiscences of Dr. DeLoughery, A.B. 1826,” The College Journal, 14, no. 5 (February, 1886): 50-51. Available in the Georgetown University Archives, Special Collections (GUA-SC).

[5] Coleman Nevils, S.J., Miniatures of Georgetown, 1634-1934: Tercentennial Causeries (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1934).

[6] Ibid.

[7] ”The Georgetown College Cadets.” College Journal. 5, no. 8 (May, 1877): 85-87.

[8] Alymer to Henry Aylmer. Georgetown, 4 November 1836, The Aylmer Family Papers, GUA-SC,. Box 1, Folder 3.

[9] James E. Poindexter, “Address on the Life and Services of Gen. Lewis A. Armistead.” Southern Historical Society Papers. 37 (1909): 144-151. BG Armistead is known as the Confederate officer who made it the farthest into Union territory. He commanded a brigade in Pickett’s division at Gettysburg. On July 3, 1863 his brigade formed the left center of the famous offensive that would become known as “Pickett’s Charge.” On the order to advance, Armistead raised his hat on the point of his sword and exhorted his soldiers, “Men! Remember what you are fighting for – your homes, your friends, and your sweethearts! Follow me!”Armistead’s brigade advanced against two Pennsylvania regiments and halted where Armistead fell. This spot marked the highpoint of the Confederacy. Ironically, Armistead on his deathbed willed his valuable possessions to his old friend Winfield Hancock, a fellow West Pointer who had fought for the North. Armistead never knew that Hancock’s troops were the very same who mortally wounded him and annihilated his brigade.

[10] “The Constitution and Bylaws of the Georgetown College Cadets,” 5 October 1852, GUA-SC, Military File, Box 1.

[11] ”The Georgetown College Cadets.” College Journal. 5, no. 8 (May, 1877): 85-87.

[12] James Ryder, S.J. ”An agreement for the release of arms issued to George Town College,” Washington DC. 9 May 1851, National Archives and RecordsAdministration, Record Group 156.

[13] Joseph Durkin, S.J., ed. Swift Potomac’s Lovely Daughter: Two Centuries at Georgetown through Students’ Eyes, (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1990).

[14] ”The Georgetown College Cadets.” College Journal. 5, no. 8 (May, 1877): 85-87.

[15] John Gilmary Shea,. Memorial of the First Centenary of Georgetown College, D.C. comprising a History of Georgetown University by John Gilmary Shea, LL.D., and an Account of the Centennial Celebration by a Member of the Faculty, (New York: P.F. Collier, 1891): 204.

[16] Joseph Durkin, S.J., ed. John Dooley, Confederate Soldier: His War Journal. (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1945).

[17] Diary entry, Francis J. Barnum, S.J. Papers, GUA-SC, Box 13, Folder 4, 36-37.

[18] It is reported, although as yet undocumented, that the college had to negotiate with the cadets to force them to parade for Grant. This coercion precipitated the dissolution of the corps sometime in the mid 1870’s.

[19] ”A Review of the Georgetown ROTC,” Foreign Service Courier, 5, no. 4. (9 November 1956): 23-25.

[20] Paper, Thomas F. Bullock, ”Men of Georgetown: The Story of our Alumni Killed in Action.” Alumni Files, GUA-SC. Dowd had graduated from Georgetown in 1908 and subsequently graduated from Columbia Law School. He joined the French Foreign Legion and served in North Africa. When the war began, he joined the French Aviation Corps. He was killed when his plane lost power over the Buc Aerodrome while training. He died on 12 August 1916 and is buried in Saint Germaine, France.

[21] ”A Review of the Georgetown ROTC,” Foreign Service Courier, 5, no. 4. (9 November 1956): 23-25. The 1940 championship was won under the marksmanship and leadership strength of Thomas MacGuire Lewis, of the class of 1940, who was K.I.A. in a plane crash during WWII.

[22] Ibid.

[23] He also set a U.S. Army service record when he threw a fragmentation grenade 104 yards.

[24] Paper, Bullock.

[25] A small Air Force ROTC contingent remained at GU until 1974.

[26] “About the Consortium [online],” Consortium of Universities of the Washington Metropolitan Area., [cited 6 August 2001] Available from World Wide Web: http://www.consortium.org/about

[27] Ellen Key Blunt,. “Bob Kennedy Walks the Red Carpet To See War Film and Gets the Point,” The Washington Post, 12 October 1962, p. A1, col. 4.

[28] ROTC scrapbooks, GUA-SC.

[29] Sara Cashen, ”Over 150 Years of Military Training,” The Georgetown Voice, 1 February 1983, 6-7.

[30] Barbara Buell, “ROTC Fast and Vigil Begins,” The Georgetown Voice, 2 October 1973, 3 & 7.

[31] Valerie Acerra, ”ROTC Vote Soon; Both Sides Firm,” The Georgetown Voice, 9 October 1973, 9.

[32] Anne Marie Ellis, ”Christine Vaishvila: Proving She Can Do It” Georgetown Today, 1978, 14-15.

[33] Joyce Shelby, ”ROTC Isn’t Just for Men,” Georgetown Today, March 1975, 11. Both Vaishvila and Siccardi belonged to the class of 1978.